The lessons that we should have learned when the CRC failed

By Ronald A. Buel of Portland, Oregon. Ronald is a longtime progressive activist in Portland. This is the third column in a four-part series on climate change and Oregon transportation policy. Read the first and second columns.

As the State Legislature convenes in Salem, it would be worth recalling the Oregon Only version of the Columbia River Crossing (CRC) and what really happened to kill it and why it died, a story that has not been told by Oregon’s press.

This little piece of recent history has lessons for our new Governor, for House Speaker Tina Kotek, for House Chair of Transportation Tobias Read, and for Senate Transportation Chair Lee Beyer. We expect this group to rush forward this session to raise the gas tax. Despite the denials, ODOT will undoubtedly begin trying to build the CRC again, as it remains first in line on the state’s priority list and first in line on Metro’s list. The Oregon Transportation Commission and the Port of Portland conceive the CRC as simply the first in a series of large road construction projects for the state.

The first shot in this increase-the-gas-tax campaign was fired at the Oregon Business Summit, attended by thousands of businessmen, and capturing speeches from both Republican and Democratic leaders. All agreed that the state’s number one issue is reducing congestion on Oregon’s highways. To support their cause, a bogus study by the Port of Portland and the Oregon Transportation Forum, which includes most of Oregon’s major business and trade groups, was cited and released to the press.

Amazingly, this study echoed the same bogus analyses and projections given by ODOT and Metro leaders to forward the CRC, analyses and projections which proved to be dramatically false. Repeatedly, again and again during the six years of public consideration of the CRC, in hearing after hearing, ODOT Executive Director Matt Garrett and Metro President Tom Hughes told all who would listen that the four to five hours of congestion at the existing I-5 bridges across the Columbia would expand to 12 to 16 hours of congestion by 2030. When the numbers actually came in for the Investment Grade Analysis needed to persuade bond-buyers that the project would work financially, it showed that from 2002 to 2013, a period of 11 full years including all six years of the public consideration of the CRC project, actual traffic across the I-5 bridges had, instead, remained exactly steady, without any growth.

So, when legislators review the bogus $1 billion projected 2040 economic cost of not dealing with congestion in the Portland region, they need to examine the projections of rapidly increasing auto traffic in the region, which have no basis in the history of the last decade. The assumption that congestion will increase with population in the region also does not stand up to careful examination, as population has definitely grown here over the last decade while overall traffic remained steady and in some cases declined. Building an economic cost based on this imaginary increased congestion is therefore quite foolish, which is exactly what the study does. Yes, drivers lose productive time in their commute as a result of congestion. But drivers have been choosing instead to ride bikes, take transit, walk, or move closer to work. And the region has been built out with an urban growth boundary that gives us a more dense urban form that requires less driving overall.

I wish this were the only lesson that should be learned from the recent history of the Columbia River Crossing. But there are several others. In blue Oregon, we should focus first on the political lessons that should have been absorbed by our state’s leaders.

-

Mega-highway projects have consequences that are often unintended. The $3 billion CRC provided four perfect examples.

-

There are only two highway bridges across the Columbia in the Portland region. The CRC proposed to replace the pair of I-5 bridges with a new bridge, tearing down the bridge(s) on I-5, which have 50 years of life left in them, especially if they were earthquake-proofed at a much lower cost. Why take out the existing capacity instead of building the new freeway bridge alongside and in addition to the existing bridges?

-

The state departments of transportation in Oregon and Washington planned to finance the CRC project primarily through tolls, which would be placed on the CRC, but not on the second crossing of the Columbia, the I-205 Bridge named after the former chair of the Oregon Transportation Commission, Glenn Jackson. The result of this, according to AW Smith, the consultant to the two departments who did the investment grade analysis for the CRC, would be to send 50,000 trips a day to the Glenn Jackson and I-205 and make that crossing as congested as the existing I-5 bridges are today. The net effect on congestion from the CRC would, therefore, be zero, not a reduction in congestion. Total vehicle miles traveled would also increase.

-

By building a big new bridge at the current location without a lift in it, the CRC would significantly hamper shipping large parts out of major existing businesses upriver and cost the states tens of millions of dollars for compensating those businesses, potentially eliminating thousands of jobs.

-

The size of the interchanges and ramps on Hayden Island and in Downtown Vancouver, and the parking lots for the light rail stations, would have taken out businesses with 936 permanent jobs.

-

-

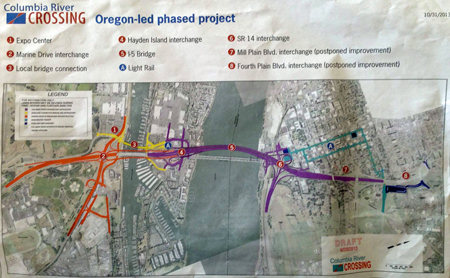

The CRC was to be over-built. This was an effort to make the highway construction, oil and auto lobbies happy, and particularly to keep the AFL-CIO and its member building trade unions happy, by providing profits and jobs with state tax monies. Starting with a $4 billion projected cost, and then cutting out two interchanges and narrowing it to $3 billion, the CRC ended up spending less than $1 billion on the bridge itself. Take a look at this drawing of the $3 billion “Oregon-led” project. Pay attention to the extent of the ramp and exchange building, costly in part because of the un-necessary height of the bridge, which could be lower if it had a lift in it. The bridge itself was to be 12 lanes wide and had shoulders of 14 feet, when the adjoining freeways only accommodate eight lanes.

-

Democratic officeholders in Portland and Vancouver misjudged opposition by Republicans in Clark County suburbs. First, Republicans are today less likely to support large government projects paid for with tax money. Second, Republicans in suburbs don’t like light rail which they didn’t see serving their suburbs (and the CRC was only sending light rail to Vancouver). Clark County, outside of Vancouver itself, has far more Republicans than Democrats. When Washington Republicans held the State Senate, first with a coalition caucus, and today with a majority of Senators, the Clark County Republicans served their suburban constituents by killing the project on the Washington side. When the Oregon Only plan came to the Oregon State Senate, Kitzhaber and Kotek found all 14 of the Republicans there opposed to the CRC, mirroring their cohorts on the Washington side. Even Republican Senator Bruce Starr, whose wife was employed by a CRC consultant, eventually became opposed. Senate President Peter Courtney quickly realized that, with an over-built project and shrinking federal highway revenues, and the traffic impacts on the districts of his East Multnomah County Senators, whose residents use I-205 not I-5, he just couldn’t get the votes in his own caucus. The final straw for the death of the Oregon Only project came when his own Democratic Senators told Courtney that Oregon would NOT have the right to unilaterally raise tolls if project finances required it but only Oregon was involved. How a few Republican Senators in Clark County get blamed for this is beyond me.

-

Hype and spin won’t always get the job done. Oregon spent nearly $100 million of the more than $200 million spent in promoting and studying the CRC. A lot of that money was spent on lobbyists who organized business and labor support and lobbied local governments and the state legislatures – Patricia McCaig, $554,000; Tom Markgraf, $1.1 million, David Parisi, $1.4 million; and EnviroIssues in Washington State, whose lobbying team was led by a former Washington State highway bureaucrat, $6.5 million. The large private company payment to McCaig, who was Governor Kitzhaber’s advisor on the CRC, set a culture of private consultancy payments that eventually brought the Governor down when his fiancee also took payments. McCaig and Hayes were close. When the Ethics Commission said McCaig had done nothing wrong taking the private money from David Evans while working in the Governor’s office, it was no wonder that Kitzhaber wanted Hayes to be judged by the Ethics Commission

-

Don’t borrow money when you can’t afford highway maintenance. Because it borrowed millions for a previous set of bridge projects, the state must now pay interest on the bonds and pay off the bonds at a cost of 30% of its total budget. ODOT has sharply cut back on maintenance of all highways, as a result. Washington State’s DOT, amazingly enough, has 70% of its revenues going to pay back bonds and interest. The CRC, financed with bonds to cover future toll revenues, and on other borrowing against other future state highway revenues, would have sharply increased the percentage of the DOTs’ over-all income going for interest and bond repayment.

|

Feb. 25, 2015

Posted in guest column. |

More Recent Posts | |

Albert Kaufman |

|

Guest Column |

|

Kari Chisholm |

|

Kari Chisholm |

Final pre-census estimate: Oregon's getting a sixth congressional seat |

Albert Kaufman |

Polluted by Money - How corporate cash corrupted one of the greenest states in America |

Guest Column |

|

Albert Kaufman |

Our Democrat Representatives in Action - What's on your wish list? |

Kari Chisholm |

|

Guest Column |

|

Kari Chisholm |

|

connect with blueoregon